#Absolutely no one does it like Euripides does it out of all A. Greek poets. To me.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hey so. Euripides was crazy for it.

#MITOLOGIA 🏛️#Absolutely no one does it like Euripides does it out of all A. Greek poets. To me.#Marital torch. Torch of Hecate lit for the shades. Torch that is to burn the funeral pyre. Torch to offer a sacrifice. :—)#euripides#iphigenia in aulis#agamemnon#clytemnestra#Walker's translation

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: As a beginner in Classics I love your Classicist themed posts. I find your caption perfect posts a lot to think upon. I suppose it’s been more than a few years since you read Classics at Cambridge but my question is do you still bother to read any Classic texts and if so what are you currently reading?

I don’t know whether to be flattered or get depressed by your (sincere) remarks. Thank you so much for reminding me how old I must come across as my youngish Millennial bones are already starting to creak from all my sins of past sport injuries and physical exertions. I’m reminded of what J.R.R Tolkien wrote, “I feel thin, sort of stretched, like butter scraped over too much bread.” I know the feeling (sigh).

But pay heed, dear follower, to what Menander said of old age, Τίμα το γήρας, ου γαρ έρχεται μόνον (respect old age, for it does not come alone). Presumably he means we all carry baggage. One hopes that will be wisdom which is often in the form of experience, suffering, and regret. So I’m not ready to trade in my high heels and hiking boots for a walking stick and granny glasses just yet.

To answer your question, yes, I still to read Classical literature and poetry in their original text alongside trustworthy translations. Every day in fact.

I learned Latin when I was around 8 or 9 years old and Greek came later - my father and grandfather are Classicists - and so it would be hard to shake it off even if I tried.

So why ‘bother’ to read Classics? There are several reasons. First, the Classics are the Swiss Army knife to unpick my understanding other European languages that I grew up with learning. Second, it increases my cultural literacy out of which you can form informed aesthetic judgements about any art form from art, music, and literature. Third, Classical history is our shared history which is so important to fathom one’s roots and traditions. Fourth, spending time with the Classics - poetry, myth, literature, history - inspires moral insight and virtue. Fifth, grappling with classical literature informs the mind by developing intellectual discipline, reason, and logic.

And finally, and perhaps one I find especially important, is that engaging with Classical literature, poetry, or history, is incredibly humbling; for the classical world first codified the great virtues of prudence, temperance, justice, loyalty, sacrifice, and courage. These are qualities that we all painfully fall short of in our every day lives and yet we still aspire to such heights.

I’m quite eclectic in my reading. I don’t really have a method other than what my mood happens to be. I have my trusty battered note book and pen and I sit my arse down to translate passages wherever I can carve out a place to think. It’s my answer to staving off premature dementia when I really get old because quite frankly I’m useless at Soduku. We spend so much time staring at screens and passively texting that we don’t allow ourselves to slow down and think that physically writing gives you that luxury of slow motion time and space. In writing things out you are taking the time to reflect on thoughts behind the written word.

I do make a point of reading Homer’s The Odyssey every year because it’s just one of my favourite stories of all time. Herodotus and Thucydides were authors I used to read almost every day when I was in the military and especially when I went out to war in Afghanistan. Not so much these days. Of the Greek poets, I still read Euripides for weighty stuff and Aristophanes for toilet humour. Aeschylus, Archilochus and Alcman, Sappho, Hesiod, and Mimnermus, Anacreon, Simonides, and others I read sporadically.

I read more Latin than Greek if I am honest. From Seneca, Caesar, Cicero, Sallust, Tacitus, Livy, Apuleius, Virgil, Ovid, the younger Pliny to Augustine (yes, that Saint Augustine of Hippo). Again, there is no method. I pull out a copy from my book shelves and put it in my tote bag when I know I’m going on a plane trip for work reasons.

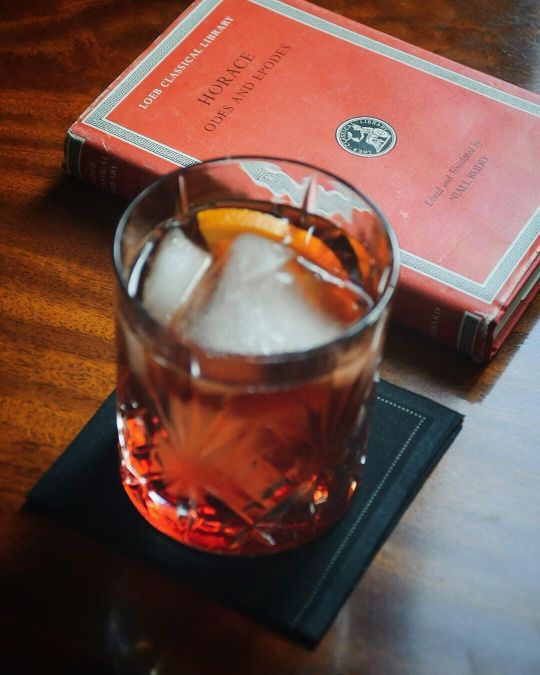

At the moment I am spending time with Horace. More precisely, his famous odes.

Of all the Greek and Latin poets, I feel spiritually comfortable with Horace. He praises a simple life of moderation in a much gentler tone than other Roman writers. Although Horace’s odes were written in imitation of Greek writers like Sappho, I like his take on friendship, love, alcohol, Roman politics and poetry itself. With the arguable exception of Virgil, there is no more celebrated Roman poet than Horace. His Odes set a fashion among English speakers that come to bear on poets to this day. His Ars Poetica, a rumination on the art of poetry in the form of a letter, is one of the seminal works of literary criticism. Ben Jonson, Pope, Auden, and Frost are but a few of the major poets of the English language who owe a debt to the Roman.

We owe to Horace the phrases, “carpe diem” or “seize the day” and the “golden mean” for his beloved moderation. Victorian poet Alfred Lord Tennyson, of Ancient Mariner fame, praised the odes in verse and Wilfred Owen’s great World War I poem, Dulce et Decorum est, is a response to Horace’s oft-quoted belief that it is “sweet and fitting” to die for one’s country.

Unlike many poets, Horace lived a full life. And not always a happy one. Horace was born in Venusia, a small town in southern Italy, to a formerly enslaved mother. He was fortunate to have been the recipient of intense parental direction. His father spent a comparable fortune on his education, sending him to Rome to study. He later studied in Athens amidst the Stoics and Epicurean philosophers, immersing himself in Greek poetry. While led a life of scholarly idyll in Athens, a revolution came to Rome. Julius Caesar was murdered, and Horace fatefully lined up behind Brutus in the conflicts that would ensue. His learning enabled him to become a commander during the Battle of Philippi, but Horace saw his forces routed by those of Octavian and Mark Antony, another stop on the former’s road to becoming Emperor Augustus.

When he returned to Italy, Horace found that his family’s estate had been expropriated by Rome, and Horace was, according to his writings, left destitute. In 39 B.C., after Augustus granted amnesty, Horace became a secretary in the Roman treasury by buying the position of questor's scribe. In 38, Horace met and became the client of the artists' patron Maecenas, a close lieutenant to Augustus, who provided Horace with a villa in the Sabine Hills. From there he began to write his satires. Horace became the major lyric Latin poet of the era of the Augustus age. He is famed for his Odes as well as his caustic satires, and his book on writing, the Ars Poetica. His life and career were owed to Augustus, who was close to his patron, Maecenas. From this lofty, if tenuous, position, Horace became the voice of the new Roman Empire. When Horace died at age 59, he left his estate to Augustus and was buried near the tomb of his patron Maecenas.

Horace’s simple diction and exquisite arrangement give the odes an inevitable quality; the expression makes familiar thoughts new. While the language of the odes may be simple, their structure is complex. The odes can be seen as rhetorical arguments with a kind of logic that leads the reader to sometimes unexpected places. His odes speak of a love of the countryside that dedicates a farmer to his ancestral lands; exposes the ambition that drives one man to Olympic glory, another to political acclaim, and a third to wealth; the greed that compels the merchant to brave dangerous seas again and again rather than live modestly but safely; and even the tensions between the sexes that are at the root of the odes about relationships with women.

What I like then about Horace is his sense of moderation and he shows the gap between what we think we want and what we actually need. Horace has a preference for the small and simple over the grandiose. He’s all for independence and self-reliance.

If there is one thing I would nit pick Horace upon is his flippancy to the value of the religious and spiritual. The gods are often on his lips, but, in defiance of much contemporary feeling, he absolutely denied an afterlife - which as a Christian I would disagree with. So inevitably “gather ye rosebuds while ye may” is an ever recurrent theme, though Horace insists on a Golden Mean of moderation - deploring excess and always refusing, deprecating, dissuading.

All in all he champions the quiet life, a prayer I think many men and women pray to the gods to grant them when they are caught in the open Aegean, and a dark cloud has blotted out the moon, and the sailors no longer have the bright stars to guide them. A quiet life is the prayer of Thrace when madness leads to war. A quiet life is the prayer of the Medes when fighting with painted quivers: a commodity, Grosphus, that cannot be bought by jewels or purple or gold? For no riches, no consul’s lictor, can move on the disorders of an unhappy mind and the anxieties that flutter around coffered ceilings.

Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt (they change their sky, not their soul, who rush across the sea.)

Part of Horace’s persona - lack of political ambition, satisfaction with his life, gratitude for his land, and pride in his craft and the recognition it wins him - is an expression of an intricate web of awareness of place. Reading Horace will centre you and get you to focus on what is most important in life. In Horace’s discussion of what people in his society value, and where they place their energy and time, we can find something familiar. Horace brings his reader to the question - what do we value?

Much like many of our own societies, Rome was bustling with trade and commerce, ambition, and an area of vast, diverse civilisation. People there faced similar decisions as we do today, in what we pursue and why. As many of us debate our place and purpose in our world, our poet reassures us all. We have been coursing through Mondays for thousands of years. Horace beckons us: take a brief moment from the day’s busy hours. Stretch a little, close your eyes while facing the warm sun, and hear the birds and the quiet stream. The mind that is happy for the present should refuse to worry about what is further ahead; it should dilute bitter things with a mild smile.

I would encourage anyone to read these treasures in translations. For you though, as a budding Classicist, read the texts in Latin and Greek if you can. Wrestle with the word. The struggle is its own reward. Whether one reads from the original or from a worthy translation, the moral virtue (one hopes) is wisdom and enlightenment.

Pulvis et umbra sumus

(We are but dust and shadow.)

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#classical#greek#latin#horace#poetry#literature#arts#cambridge#classics#personal#study#habits#reading#books#culture#personal growth

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Truth, justice, or whatever

Is there such a thing as a self-respecting philosopher? Aristophanes, in The Clouds, made the philosopher into an object of derision: impractical, impoverished, devoid of common sense and emotional intelligence, and so obsessed with metaphysical esoterica as to be incapable even of self-care.

Against such formulations, how does the philosophical nerd stand up for himself? His prognosis seems to improve when we recall that his natural enemy is not the jock but the poet — not himself known for practicality. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates famously describes the “ancient quarrel between poetry and philosophy,” started of course by the poets, when they made fun of philosophers.

For those who can’t decide which side to take, there is the third way practiced by Nietzsche: to enter the battle on the side of the poets but as a philosopher. This is the spirit of Simon Critchley’s Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us. The book is not merely an account of ancient Greek tragic drama (and its relevance for us) but also an attempt to turn Plato’s famous critique of the poets back on itself: Philosophy must be corrected by “tragic consciousness.”

No one who has set foot in a philosophy classroom will be surprised by Critchley’s recital of what he calls “philosophy’s tragedy”: It overestimates the power of rational reflection to obtain knowledge of the world and ourselves. It establishes metaphysical and moral absolutes. And it overestimates our agency — our ability to act freely on the basis of reasoning about what is right and good. These anti-philosophical tropes have been in fashion since the beginning of philosophy and have reached their apotheosis in the fusion of critical theory and post-structuralism that now dominates the humanities and social sciences. In fact, they are increasingly influential in public discourse: Critchley himself is the moderator of the Stone, the New York Times's philosophy forum.

Will an analysis of tragedy add something further to such well-worn complaints? Critchley is particularly insistent on the idea that philosophy is devoted to a “non contradictory … psychic and political existence” that has no place for the feeling of grief. This describes the position of Plato, whose Republic attacks tragic poetry for encouraging audiences to identify with the spiritual conflict and sorrow of the poems’ protagonists. Such identifications, Plato warns, allow us to take pleasure in painful psychical states, which means that pain then overwhelms our rational capacities and no longer serves as the proper corrective to bad behavior. Instead, we are encouraged to indulge in our sorrow, mimic the psychological disorder of protagonists, and write off our own conflicts as part of a hopelessly irrational human condition.

One might attempt to defend tragedy by challenging Plato’s rather simplistic rendition of identification, in which the audience simply incorporates represented mental states whole cloth. We get the seeds of a more robust account in Aristotle’s Poetics. Particularly important here is the concept of catharsis, which suggests that tragedy can actually purge us of the emotional states it elicits instead of leaving us with their permanent detrimental effects.

Critchley does not like this sort of account, nor does he like various attempts to deepen it: Catharsis, in his view, is not purgation, nor is it purification, emotional recalibration, psychotherapy, or any sort of moral education that leads to greater “psychical integration” or “authenticity.” He has no argument against such understandings except to say that they come dangerously close to having something favorable to say about the possibility of human autonomy and self-knowledge. His preferred view, tragic consciousness (or “tragedy’s philosophy”), is concerned with the ways in which we are irredeemably compromised by fate, understood as any force (social, psychological, or divine) that exceeds our capacity for deliberation. Our agency and self-knowledge are never more than partial.

In Critchley’s view, a protagonist’s tragic flaw symbolizes human fallibility and finitude. The tragic hero is essentially conflicted, “at odds with himself, doubled over and divided.” So is the audience, and so is “the city of which the tragic hero is both the expression and symptom.” Tragedy forces us to recognize both our limited agency and the world’s incomprehensibility and moral ambiguity. “Tragedy’s philosophy” turns out to be “a bracing, skeptical realism” that stares down a world “entirely without the capacity for redemption.”

There’s much more to this account, including Critchley’s praise of Plato’s other well-known antagonists, sophistry and rhetoric. The last section of the book is devoted to Aristotle’s Poetics and rejects its focus on coherence and organic unity in favor of Euripides’s “tragedies of disintegration, disunity, and incoherence.”

Unfortunately, Critchley’s distaste for coherence is clear in the way his book is structured and written. It consists of 61 brief chapters of disjointed rambling that at times verge on mania, as if Holden Caulfield lost his mind after attending a graduate postmodernism seminar. It combines ham-fisted attempts at being accessible and relevant with all the pretentious tics of contemporary continental philosophy. Pop culture references abound, and an alarming number of sentences end with “or whatever” — as in “truth, justice, or whatever.” But if you need any reassurances about the author’s sophistication, you’ll be treated to many a “horizon,” “doxa,” “otherness,” and “lacuna.”

This is all to say that the book is full of the counterproductive effects that follow from a philosophical bad conscience — from Critchley’s attempt to disavow a simplistic conception of philosophy in order to ally himself with a simplistic conception of the poetic. In doing so, the book sacrifices both philosophical depth and literary sensibility.

What substance the book has it borrows from a handful of well-known secondary sources. It reports these sources faithfully but makes no attempt to analyze, synthesize, or otherwise critically engage with them. Meanwhile, it represents philosophy in general as a form of dogma — a straw man devoid of the nuance to which “tragic consciousness” is supposed to attune us. Contra Critchley, philosophy has always sought to grapple with its own fallibility. Socrates, after all, claimed to know nothing, and his willingness to die for it was tragic.

If you can’t be friends with philosophy, you ought to at least make friends with psychology. Whereas Critchley identifies “affect regulation” (or our ability to manage our emotions) with reason’s repression of emotion, depth psychologists think of it as the capacity to have emotions without being overwhelmed by them: One contains them. This in turn requires a capacity to represent feelings, to put them in thoughts and words, instead of disavowing them only to enact them tragically. And this capacity is thought to be a product of growing up, a process in which loss and mourning are essential. We give up the ministrations of our early caretakers only to internalize the ability to take care of ourselves.

The insight of the depth psychologists is that integration and disintegration, much less reason and emotion, do not form the binary opposition that Critchley thinks they do. The experience of loss may involve an integration of what is lost and forms the basis of the identification at work in an audience’s experience of the tragic. This sort of account is essential to deepening our understanding not just of catharsis but also of the aesthetic. If we can understand the relationship between external losses and internal gains, we are in a much better position to explain the pleasures of tragic consciousness and defend them against anti-poetic mania.

Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us, by Simon Critchley. Vintage, 336 pp., $16.95.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

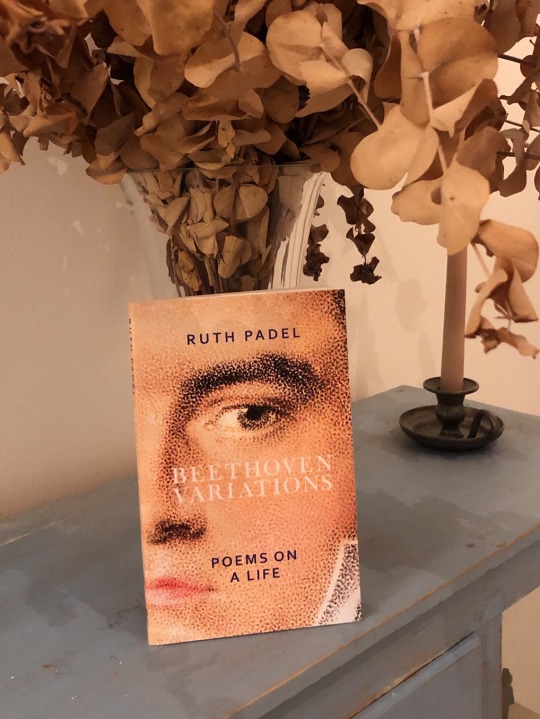

Interview with Ruth Padel

Ruth Padel is an award-winning poet who teaches as Professor of Poetry at King’s. She has published over 20 books, 13 of which are poetry collections. The King’s Poet’s Karen Ng talks to Ruth about her new collection, Beethoven Variations: Poems on a Life and her experiences as a poet.

How did you first realise you wanted to write poetry?

I enjoyed poetry as a small child and found I knew poems by heart without trying to learn them, so I started writing them. It was natural, like singing.

How much of a relationship is there between music and poetry? Poetry is music! What influence does music have on your poetry? Does it play an important role in your life?

I grew up playing piano, and viola – like Beethoven – and singing. The first money I ever earned was £5 playing viola in Westminster Abbey. There were professional musicians in my father’s family. His grandfather was a piano soloist born in Christiansfeld, south Denmark, who studied at the Leipzig Conservatoire with Beethoven’s pupil Ignaz Moscheles. In 1868 he settled in York, teaching and playing. His son, my grandfather played violin and as headmaster of Carlisle Grammar School established a vigorous school orchestra and a family string quartet, a tradition that my dad continued with all of us. But I’ve also always sung, wherever I’ve lived: whether this was Cretan mantinades with workmen in the archaeological trenches at Knossos, or in more formal settings, in choirs. And – for a couple of evenings, unpaid, in an Istanbul nightclub.

Can you tell us about your new collection Beethoven Variations? What inspired you to write about Beethoven?

Inspired isn’t quite the word – it snuck up on me! I wrote poems for a Beethoven concert, to read between an early and a late string quartet. I focussed on the twenty years of Beethoven’s life between writing the early and the late and it went great in performances. Audiences said the poems deepened their experience of the music, which was wonderful, and a great, unexpected compliment. But I knew the poems weren’t finished, and kept them on the back burner while I wrote two other collections. Writing those – one a poetry narrative called Tidings, the other lyrics on my mother’s death but recalling her life – fuelled me to tackle the story of Beethoven’s life.

I began by visiting his birthplace in Bonn, and wrote the book in 2019, on sabbatical in New York. It helps to put a perspective distance of some kind between the experience and the writing of the poem. I reworked the original poems, responding to his life but also his evolving work, in four sequences like the four movements of a traditional quartet. I whittled these down to twelve poems in each of four sections, thinking of the architecture of a quartet – like Eliot’s Four Quartets – and using my own musical life as an example of someone influenced by Beethoven, by playing him. So I threaded glints of my life through the poems, playing music but also searching for him in the places where he lived. I added an introductory poem, Listen – the thing Beethoven became unable to do, but which is absolutely crucial in playing together – about the way my parents met, through playing music.

Above all I wanted to get across his personality, the vivid counterpoint between his cut-offness – he was ruthlessly focussed on creating – his suffering, the awful deafness, his impatience, rows with everyone and devastated disappointments, and his warmth, liveliness, love of conviviality and jokes.

Behind it all, though, is Europe, his and mine. He grew up in Bonn, in Germany, on a street which dead-ended at the Rhine. He used to gaze at the river through a telescope from the attic, and was fascinated by the largest hill beyond – the Drachenfels – which he eventually climbed. So I crossed the Rhine and climbed that too, and then I followed him to Vienna when he went just as Austrian armies were mustering to fight Napoleon. The Europe he’d grown up with was changing very violently and so was mine. This was the year before Brexit, with right-wing factions – primed against immigration – growing in Austria, Poland, Hungary. The dark rifted history of Vienna, that white imperial city, ancient heart of Europe, along with the holocaust, and psycho-analysis which was born there – all that gets into the poems.

So does the contrast between the glamour, the gilt, creamy spaces and carved stone curlicues of the great palaces of Vienna, owned by rich feudal nobles – many of whom commissioned his best pieces - and the poor dark ordinary homes to which the musicians returned after they played in the glittering halls. A whole hidden history of social injustice, exploitation, and the inequality Beethoven railed against all his life – he yearned and burned for humanity to be free of it – is built into the beautiful architecture he walked through every day, the very fabric of those wonderful cities.

So, it’s a book of poems on a man’s life, someone who was the great artist of hope, the epitome of enormous creativity coming out of suffering. It is in four sections. His life from birth to twenty-two, then to thirty-two when he was making his name, thirty two to forty two, when he said farewell to love and the ‘Immortal Beloved’, whoever she was, then on to fifty-six, when he died. Followed by a prose coda of Life Notes which I wrote just to underpin the poems historically, but they mutated into a prose sequence on their own: a narrative which functions as indirect commentary or supplement to the poems but is also a standalone mini-bio.

You have written biographical poetry before, in Darwin: A Life in Poems. How does the writing process with this type of poetry differ from others? Moreover, as A Life in Poems can be considered a family memoir as well, how did the writing process differ from Beethoven Variations?

I wrote the Darwin book in a very few months, my editor wanted to bring it out on his 200th birthday, February 12th 2009. A lot of the poems incorporate his words in letters and writing. Though the introduction mentions me and my granny, his grand-daughter, I don’t put myself into those poems so it is not really a memoir in that sense. Whereas with Beethoven I bring my own musical life in, as an example of the way Beethoven’s music lives on in all of us..

Can you tell us about influences on your writing and how have your influences changed over the years?

Everything is an influence, but the poets were Kipling, very young, from the Jungle Books, then Tennyson, Keats, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath, Heaney, Charles Olsen, and on. But also the Greek poets, from Homer to Seferis.

You studied Classics and Greek poetry at university. Do the ancient poets influence your writing?

Yes. Especially Homer, Sappho and the tragic poets, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides. I spent twenty years studying them for my PhD and two books, In and Out of the Mind and Whom Gods Destroy: their words and thoughts got into me at every level.

What do you think modern writers can learn from the likes of Sappho and Homer?

Intensity of imagery, the crucial, precise relationship of words to each other, linguistic excitement, and always to address the big things through particulars. How poetry inheres in our relationships – to each other, to the natural world, and to the motivating causes of what happens to us, which might be our own emotions, or the gods. And how your job as a poet is to keep finding new words, the truest words, to explore all that.

Do you enjoy translated poetry? When “lost in translation”, can nuances in the original language ever be retrieved – without yourself, as reader, learning the language?

Translations of Anna Akhmatova, or Mandelstam, are among some of the most iconic and influential poems of the twentieth century. Different poets translate differently well. The Greek poet Seferis, for instance, often translates very well, while people are always trying to do Cavafy differently and in a way failing. Yet Cavafy is really the greater poet. It varies. But of course we need to read translations, to expand our sense and knowledge of the possible.

What do you enjoy the most about teaching poetry?

When you see someone suddenly get it, and the poems suddenly burst with real unique life. But also in class, when students work together generously as a team, and start to notice and bring up about each others’ poems points you might have picked up on yourself – but also things you would never have seen and thought of. That’s wonderful – when students say things you would never have got to on your own. When you know they are travelling, they will be ok.

Do you think poetry is sometimes perceived as an inaccessible art?

I addressed the idea of poetry being ‘difficult’ in two books written out of the columns I wrote for several years for a Sunday paper on reading poetry, 52 Ways of Looking at a Poem and The Poem and the Journey. I pointed out that it is not more difficult than we are! We are difficult creatures, our lives are difficult, so is the world we live in. Complex and difficult – shouldn’t our poetry be up to us, in ourselves?

One problem poetry has today, as compared to, say, the 19th century, is that other arts and media have taken over some of the roles it used to fulfil. Film, popular music, TV. But it can still do something nothing else can, offer a memorable, intense new way of seeing the world and your own experience, in distilled, concentrated words that really grip you when you come upon them.

How important do you think writing communities are, in fostering ‘better’ writing? In your experience, is writing helped by discussion?

Yes, yes yes! But also no. Workshops, in which a bunch of you – who trust each others’ judgement and generosity – offer help on each others’ poems, are a wonderful way to grow as a poet and learn how to read and critique as poets, how to see where each poem can work more convincingly. A place to discuss your poems and the principles behind them, and also new work you are reading. That’s the situation we try to replicate in seminars at King’s. But you also have to be on your own with the work, do the thinking, experiencing and writing on your own. The ideal is a dolphin-like progression through the waves. Up with the others in the air, but also down under the water alone.

Does poetry always benefit from constant re-drafting and experimentation?

Yes.

Do you think poets should make a habit out of writing every day?

There’s no ‘should’ about it, if you want to write well, and better, you will.

Do “sentences that sound poetic” or flowery writing always indicate good writing?

No!!! That’s a terrible word, that word poetic. Poets don’t use it. It usually means warm and fuzzy. And facile.

Does a writer need to have natural talent?

Of course. You can acquire craft, but you have to have an ear and an instinct too.

Is practice and growth more important?

Also of course!

What are your thoughts on spoken word poetry?

Its effects depend very much on the presence and voice of the poet-performer, the physical sonic relation with the audience.

Do you a favourite literary journal, or a poetry platform you would like to recommend?

Our King’s poetry journal Wild Court has reviews and essays as well as new poems from international poets, and also supports our event series Poetry And... – which I explained in the Guardian, when we started it, aims to illustrate poetry’s connectivity to all areas of life and learning. We are setting up the next Poetry And... for May 13th: Poetry And Obisidian. It will feature three poets who are among the first alumni of the Obsidian Foundation for emergent Black poets, set up by prize-winning poet Nick Makoha, currently doing a Poetry PhD at King’s. Wild Court is now beginning a slot for King’s work too. Post-graduate from our PhD Creative Writing students, and Undergraduate from students who have completed poetry modules, in consultation with the Editor and Creative Writing tutors. Wild Court aside, Poetry Review with its brilliant series Behind the Poem, Poetry London, Prac Crit and The Scores all have excellent new work.

0 notes